Wyvern

Wyvern

About

- Username

- Wyvern

- Joined

- Visits

- 3,238

- Last Active

- Roles

- Member

- Points

- 5,515

- Rank

- Cartographer

- Badges

- 24

-

Community Atlas: Constructing Errynor Map 40 - Faerie Land

While I know some folks that comment and contribute here like to present and view Work In Progress topics, I rarely map in a way that allows this, as I tend to simply change things as I'm going along and don't record what's been done or when. It also needs extra time and effort, which is something I rarely have available either. However, when I started the second of the 40 250 x 200 mile maps for "my" corner of Alarius, that did seem a rare opportunity to try to do a bit more in this line. So while not a WIP thread as such - because the map's already completed, and will be submitted for the Atlas shortly - it may be of interest to some to have an overview of how it got to be as it is.

When I started preparing for this whole Errynor project, one of the first things I did was to set up the grid for where the 250 x 200 mile maps were going to be on Shessar's Alarius map:

I then hand-drew onto squared paper details extracted from this map for each of the planned 40, including things like where the exact lines for the different background terrain fills lay on land, where the edge of the contour-colour fills were for the sea, and so forth. Although these wouldn't be so critical for the later mapping (the edges of the fills being softened in the map as shown above here means there will always be a degree of leeway in such things), they were important for some of the more detailed features I wanted to add, such as creatures which tend to be biome-specific.

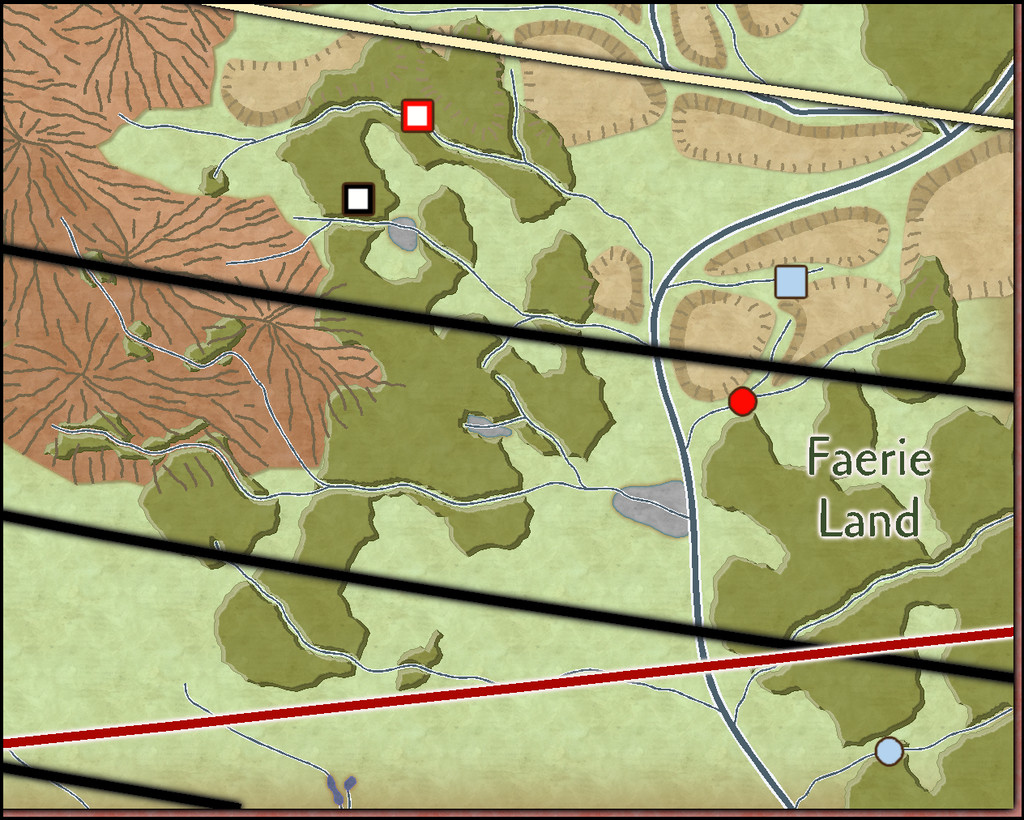

Zooming in to the Map 40 area (lowest right corner of the full gridded map above) showed what I'd be dealing with here:

The yellow line that's just peeping out from under the lowest outer orange line is for the southern limit of the Errynor mapping area (it also extends up the right-hand edge of Map 40, but is better hidden there), while the thinner white line extending south of the right-hand corner of Map 40 is because when this mapping began several years ago, the area east of Errynor had been reserved by another Atlas mapper. Ultimately, the person who was hoping to map that region had to drop out unfortunately, but Shessar subsequently stepped-in and completed part of it, although that no longer extends south to the southern edge of my Errynor area, as a comparison of where the major river (now named as the Faerie Run) lies in relation to the lowest corner of the illustrations above and below this paragraph. On the following extract from the bottom left corner of Shessar's "Alarius North Central" map, I've added a 250 x 200 mile orange rectangle for scale:

The left edge of this rectangular area immediately adjoins part of the right edge of my Map 40, and also part of Map 32 to Map 40's north.

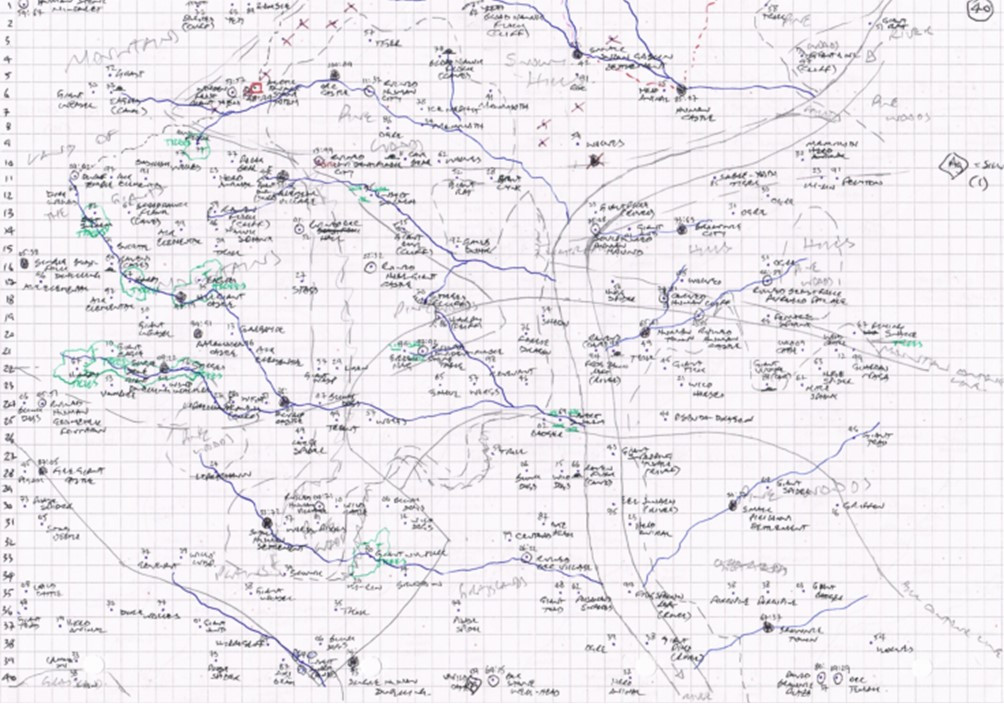

Returning to Map 40, to the hand-drawn map of landforms and terrain features, I added randomly-rolled creatures and places using a series of tables based on ones I'd constructed decades ago, updated and amended here where that seemed necessary. The squared-paper maps had been designated so that every square would be five miles on a side, and each 5-mile square was allocated a maximum 10% chance of having something noteworthy in it at this mapping scale (variably reduced for anything less favourable than temperate surface land conditions). Of those features, about 17% - 1 in 6 - might be settlements of some sort, with a maximum 60% chance of being inhabited, or deserted/ruined otherwise, again partly condition-dependent.

All of which got me to the point where I could also begin filling-in some of the lesser terrain features based on what had been rolled-up. Settlements need a significant water supply, as would some types of creature, which allowed new river lines to be sketched-in. Certain creatures also need a lair of some kind, and that meant smaller areas of cliffs, caves, trees, marshes and lakes could be added, all again based on random rolls determined by the creatures in question. Thus the map came to look like this:

This isn't very clear at the size suitable for the Forum, and the scan I made of it has cut-off the column numbering along the top edge. This wasn't important for what I intended, as it was simply meant as the traceable background bitmap image for the CC3+ map. I can't re-scan it like this, as it's been further amended since, and indeed right into the creation of Map 40 in CC3+ changes were still being made, not all of which ended up on the hand-drawn version anyway! It is still possible though to see this is a "warts and all" sketch, with crossings-out, amendments and annotations. Even the original map isn't as clear as it might be now, and I can't remember which of the various lines represent which terrain type in places where the annotations have become too dense! Note too that the line of the map's only major river (that is, the one shown on the original Alarius map) hasn't been finalised here. It's still drawn at the scale it was, so is about ten miles wide, hence why the new tributaries end at its edge. As this also illustrates, the size of the paper means the edge of the mapped area is seven squares short of this image's right-hand edge.

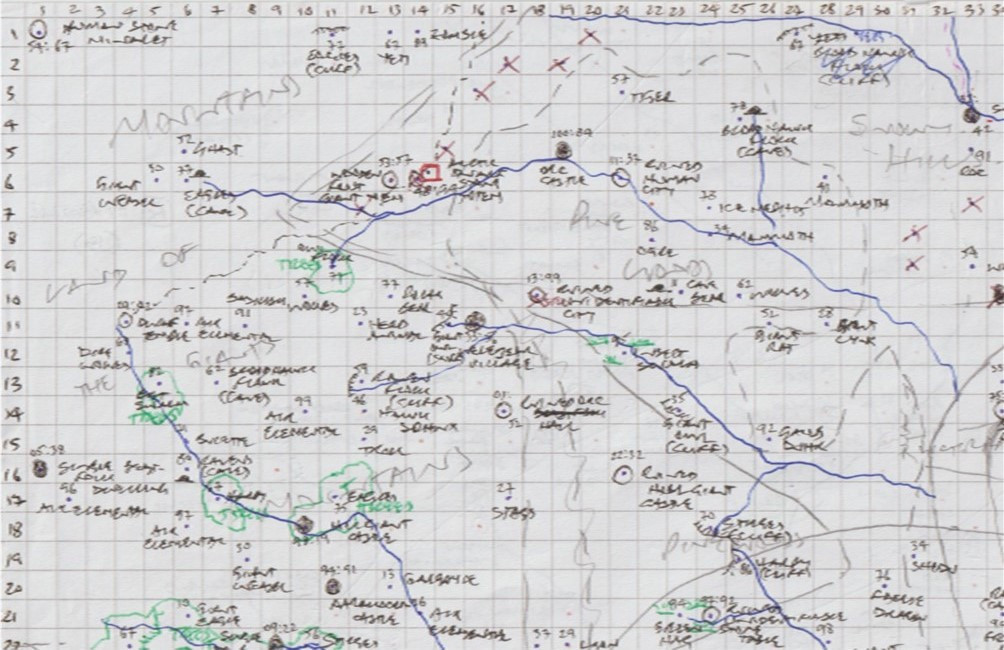

Features were allocated one or two numbers as well as a written note of what each was, as I learnt early on the importance of recording these (they're the dice roll values) after making some mistakes in identifying which thing was in which terrain type, and thus what the random tables said it was meant to be... In the map's centre-top, that Yeti that became a Blood Hawk Flock with a cliff lair turned out to have been a Yeti after all, as you may be able to tell from this close-up of a later version of just the top left corner (now so you can see the top column numbers too):

If you can see some dots that don't have any annotations, or other faint markings, that's because I hand-drew all these maps on both sides of the paper, and occasionally that shows through weakly.

Selecting only the main features, such as the major settlements and ruins, as well as the new lesser watercourses and vegetation areas, was what let me build-up the final Errynor map, of which the Map 40 segment is shown below, here with its latitude lines and the southern limit for Nibirum's northern polar auroral zone (red arc). Only the cream-coloured latitude arc, for 55°N, features in the Atlas CC3+ Errynor map. The black arcs for each 1° were added in preparation for these individual 250 x 200 mile maps, and will feature there:

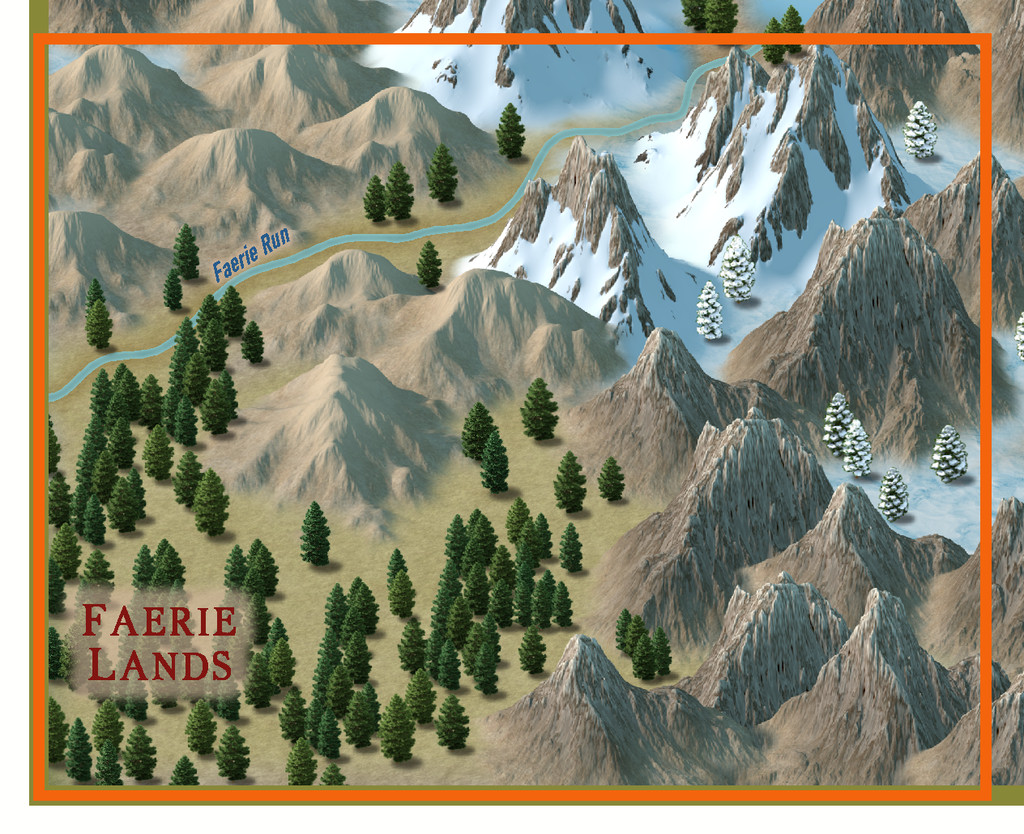

I'll present and discuss the final CC3+ map for the Atlas in more detail in a subsequent Forum topic. For now, merely a teaser view of the final Map 40's terrain (only) - no settlements, or creatures, or anything else. Yet!

-

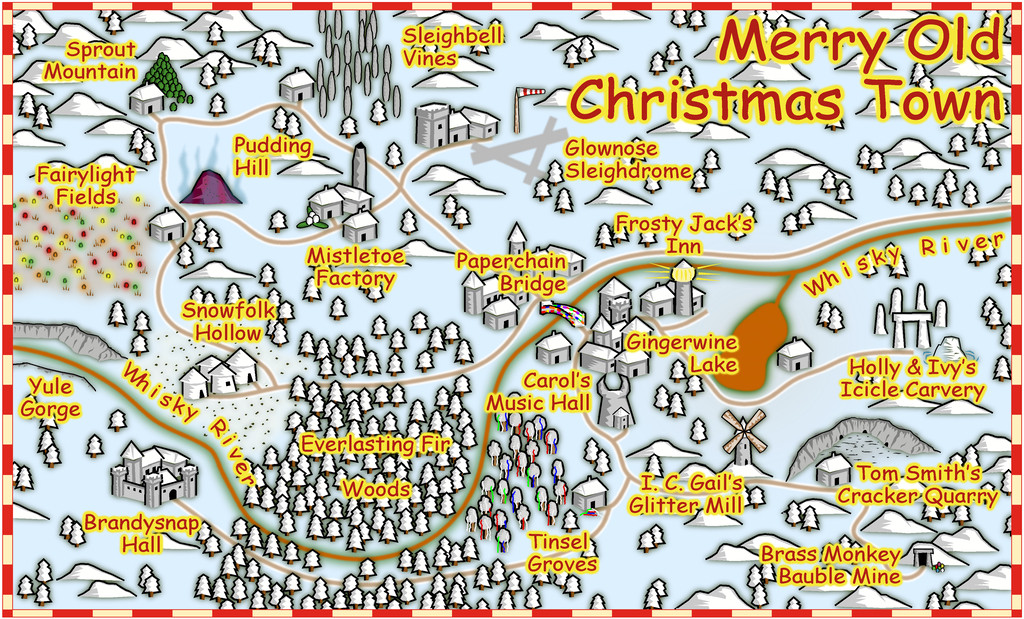

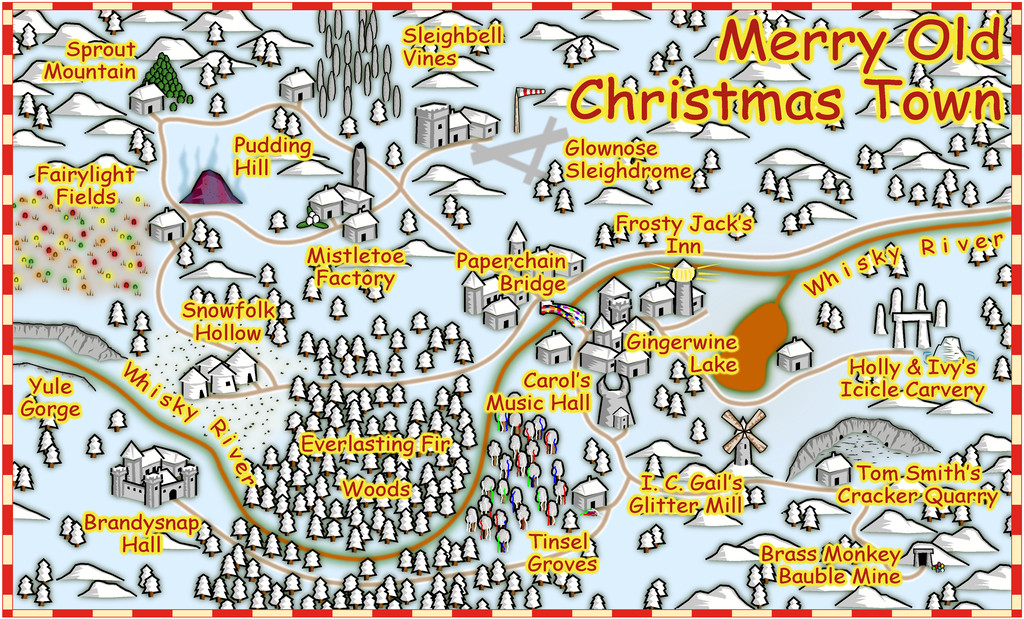

Festive Winter Card Challenge - Ended - Please vote for your favorite

This is my somewhat unexpected entry for this contest; unexpected as when it was announced I was, and indeed remain, deeply involved with the next part of my Nibirum mapping project for the Community Atlas. As explained elsewhere on the Forum though, once you start having ideas it's difficult to escape their implications...

So, here we have Merry Old Christmas Town, sort-of British-style:

I've added a higher-res version to my Gallery as well, albeit this one's not come out too badly at the usual Forum maximum size, as the style seems to cope quite well with increased anti-aliasing without becoming too large.

Just to clarify, this was prepared using ONLY CC3+; there's been no post-processing of any kind.

Feels slightly weird not to be submitting the map for the Community Atlas as well for once!

-

Festive Winter Card Challenge - Christmas Town

When @Monsen announced the latest Forum mapping contest, for a (winter?) holiday-themed postcard-sized map, I was deep in the latest part of my Community Atlas mapping project for Nibirum, and indeed still am, so wasn't sure if I'd have time to do something useful for this as well. But you know how it is when you start having vague ideas for something...

Thus away from any CC3+ mapping, I jotted down a few silly place-name thoughts. Since some early comments on the contest topic had suggested something holiday-themed appropriate to the place of origin would be suitable, I focused into aspects of the Christmas period in Britain, which of course include ghastly jokes, puns and other nonsensical daftness. I'm not sure how far all these may survive beyond these shores; however, it's too late now, as the map's done!

My original list of nearly 40 place-names was quickly halved, given how small a postcard-sized map would be, and then being me, I sketched-out by-hand on squared paper where all these places were going to be in a rough sense, based on random dice rolls. The square sizes were chosen based on an estimate of the size the symbols would be on such a small map, to hopefully avoid over-crowding.

I'd already decided I wanted to use the standard CC3+ Overland Vector Color style for the map, as I have a fondness for vector styles, and this overland style in particular. Vector symbols have the advantage it's often quite possible to add-to, amend or adjust existing symbols, or even create new ones, without them looking too awful, given my legendary lack of artistic ability...

When I began, I had the loose notion I might try and take a few screenshots for a WIP topic here, though I soon forgot all about that unfortunately, as the map started to come together remarkably quickly, after a few early tweaks to get the symbol sizing to look right. I created a few fresh tools, and tinkered with the Effects in places, though nothing very major or time-consuming. The latter needed adjusting mostly because the Effects had been set for a much larger mapping area, of course, while the former needed adding because for some unaccountable reason, the style's designer hadn't prepared for drawing whisky rivers and snowy roads in advance. Some people are strange 😉

Handily though, the style's symbols all have really helpful varicolor options for being snowy-frosty white in just the right places (with a couple of minor exceptions, where a few snowy flatter roofs had to be added by-hand). In barely a couple of hours, the basic map was done. It needed a few fine-tuning adjustments, but the longest task, once all the labels were added, was trying to work out the better colour combinations for those labels and their Glow Effect, so they'd stand-out nicely, without being overwhelming. That dragged on for over an hour, to the point where I'm sure I ended up more or less where I'd started!

And so we have Merry Old Christmas Town, British-ish style:

-

[WIP] Modern city map

-

Community Atlas: Errynor - Aunty MacKassa's Home & Vehicles